Ban on Luxuries – Voluntary as well as Obligatory Contributions to State Funds – Keeping intact Individual Initiative – Value of Voluntary Contributions – Example of Early Islam

So far, therefore, as luxuries and indulgences are concerned, Islam brings about equality by prohibiting them altogether. It is obvious that States and systems which seek to provide luxuries and means of indulgence for all classes are bound to embark upon exploitation of their weaker neighbours. As against this, States, which aim at uniform standards of simple living, have only to persuade the wealthier sections of their own people to adopt simpler standards. It is very much easier to enforce and maintain standards of simple living than to set limits to luxury and indulgence. The standard of equality aimed at by Islam is much more easily attainable than the standards which the European and American communities have set themselves. Islam can succeed in bringing about reconciliation between the classes in providing reasonable standards of comfort for everybody at much less expense than would be the case with other communities. On the one side, the object is to provide luxuries for the poor as well as for the rich, and on the other, the object is to make adequate provision for the necessaries of life for the poor and to prohibit luxuries and means of indulgence to the rich. Islam can restore peace and comfort to mankind with much less effort and expense than is possible, for instance, for Christianity. Islam prohibits the wearing of silk by men; it prohibits eating and drinking out of vessels of gold and silver; it prohibits the erection of stately buildings for the sake of pomp and show. Similarly, it prohibits Muslim women from spending large sums upon ornaments. It makes the drinking of wine, gambling and betting unlawful. The object of these prohibitions is to enforce simple standards of living among the rich so that they can be persuaded to contribute their surplus for the relief of the poor. On the other hand, the poor would have no desire to indulge in these luxuries as they will have no temptation to imitate the rich in respect of them.

Again, Islam provides scope for individual effort, encourages it and seeks to induce the rich by persuasion and moral exhortation to make voluntary contributions towards the relief of the poor. I have already pointed out the injurious results that are bound to flow from the suppression or discouragement of individual effort and initiative and also those that are bound to result from violent and compulsory dispossession. Universal peace, comfort and happiness can be secured only under a system which keeps alive individual effort and initiative and secures adequate means for the relief of the poor by persuasion. This is what Islam aims at. Other movements generally advocate compulsory acquisition of all surplus wealth. But apart from the recovery of compulsory taxes, Islam does not permit compulsory acquisition. It proceeds by the method of persuasion which results in an increase of goodwill and affection between the different sections. If a rich man is deprived compulsorily of his surplus wealth, he is not likely to feel much affection towards those for whose benefit he has been so deprived, nor will the poor under such a system have any particular feelings of gratitude or affection for the rich. If, on the other hand, a person voluntarily devotes his surplus wealth towards the service of humanity, he is bound to be inspired by feelings of benevolence and affection towards others, while those who derive benefit from the application of his wealth to their service are bound to hold him in esteem and affection. This method is calculated to promote universal goodwill between different sections of mankind.

The encouragement of individual effort will ensure that everybody will follow his own particular pursuit or occupation with diligence, and this must result in continuous intellectual progress. A physician will try to achieve the highest success in the art of healing, an engineer will aim at getting ahead of fellow professionals in his particular branch of engineering, a manufacturer will try to improve his methods so as to secure the highest yield at the lowest cost and so on. If each of them is further persuaded to contribute generously towards the service of their fellow-beings, the necessary funds will be secured while maintaining intellectual progress, and without occasioning any resentment or bitterness. Bolshevism, as I have said, tends to arrest intellectual progress and the method of compulsion employed by it creates bitterness in the hearts of those who are dispossessed of their property. Against this, if everybody is permitted and encouraged to exercise his particular talent to the utmost extent, a physician in the art of healing, a lawyer in the courts of justice, an engineer in the thousand and one activities that require the exercise of his skill, and they are then asked voluntarily to contribute out of their surplus towards the relief of their less fortunate brethren, they will experience no feelings of injustice or bitterness, but feel satisfaction and happiness of being able to serve the cause of humanity. This would maintain justice and fair-dealing and promote benevolence and goodwill all round.

Contrast with this the feelings of a person whose earnings or property are taken away from him compulsorily by the State. He will experience no surge of benevolence towards the poor. In fact, a sense of injustice will always rankle in his mind and he will always be ill-disposed and disaffected towards a system which constantly subjects him to such treatment. On the other hand, the poor will have no feelings of gratitude in the matter. They will be disposed to imagine that the mere fact of a man being rich showed that he had been unjust and dishonest and that it was a good thing that he had been compulsorily deprived of his surplus property. Under a voluntary system, a rich man will contribute towards the relief of the poor, but there will be no feeling of injustice on the one side or hostility on the other. These will be replaced by benevolence and goodwill.

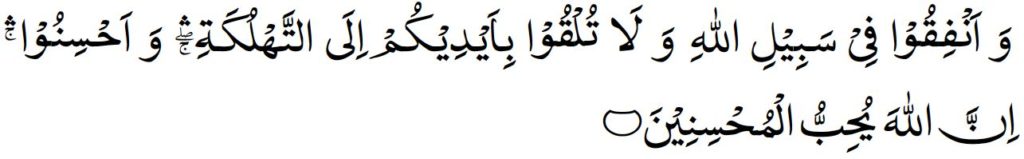

This is the method adopted by Islam. It imposes taxes for this purpose by way of Zakat and ‘Ushar, and then supplements them by the injunction:

“And spend for the cause of Allah, and cast not yourselves into ruin with your own hands, and do good; surely, Allah loves those who do good.” (2:196)

That is to say, in addition to compulsory taxes you must make voluntary contribution towards the relief of the poor, and must not by failing in this duty provide for your destruction. This means that those, who have a surplus of wealth, will suffer no real loss by contributing towards the relief of the poor, but that if they do not do so, they will in the end themselves be destroyed. This verse clearly tells of the fate of the French and Russian aristocrats. Failure by the rich voluntarily to discharge this obligation is bound in the end to entail their own destruction. The common people would rise and destroy everything in their blind rage. In the language of Shahpur district they would “say the final prayers” over the wealth of the rich. Our Khalifatul-Masih I, the First, used to explain this as meaning that in the Shahpur district, the peasants go on borrowing from the money-lender and their indebtedness increases steadily until the whole tract becomes heavily indebted and all their earnings are appropriated by the money-lender towards the interest due on the loans. When this stage is reached some big landlord in the locality collects the peasants together and inquires from them what the amount of their indebtedness is. Each specifies the amount due from him, and the landholder then inquires whether they have any means or hope of repaying. Everybody expresses his inability to do so. It is then proposed that the matter should be settled by “saying final prayers.” All of them pray and arming themselves with various weapons proceed to the house of the money-lender, put him to death and burn all his papers and books.

In this verse God enjoins that those who have surplus means should employ them in the service of humanity and should thus save themselves from destruction. In other words, Islam permits the acquisition of wealth by proper means but forbids storing it up, as this would ultimately lead to revolution and destruction of property. The verse then proceeds to say:

‘And do good to others.’

That is to say, it exalts Muslims to go a step further by reducing their own requirements and spending the money thus saved in the service of humanity. It enjoins, however, that this should be done cheerfully and not out of the fear that surplus wealth be destroyed otherwise. The object should be to win the pleasure of God. If this teaching is followed in order to win the pleasure of God, it would afford happiness to the poor, safeguard the rich, and win divine pleasure for them. The verse concludes:

‘Surely Allah loves the doers of good?’

That is, you should not imagine that in acting upon this teaching you are being deprived of the wealth that you have lawfully earned. This would, in turn, prove a profitable investment which would win for you the Love of God, improve society in this world, and secure reward for you in the next. In other words, you will secure comfort and happiness both here and the Hereafter. This teaching safeguards individual effort and enterprise on the one hand, and secures the uplift of the whole of society on the other, the latter being also the declared object of Bolshevism.

It may be said: “This is very well as a teaching, but what we want to know is whether Islam has ever succeeded in providing food, clothing, shelter, medical relief and means of education for the poor. If it has ever succeeded in securing these conditions, we should be told how the system worked in practice.” In answer to this, it is important to realise in the first place that only that teaching can be successful which is able to deal with conditions arising in each succeeding age. It should possess enough elasticity to be able to achieve the ideal which it sets before us according to the circumstances of each age. An absolutely fixed and rigid system may prove beneficent at one time, or in one place, but may cease to be of any use at another time or another place. It must be able to adjust itself to the changing circumstances of human life. By elasticity, however, I mean elasticity in application, not in principles and ideals.

In the early days of Islam, the social and economic teachings of Islam proved fully equal to the demands made upon it. The Holy Prophet(sa) not only insisted upon simple modes of living but as soon as Muslims achieved political power, history bears witness that the needs of the poor were fulfilled from Zakat supplemented by voluntary subscriptions. In this connection the Companions(ra) of the Holy Prophet(sa) used often to make great sacrifices. Hazrat Abu Bakr(ra) on one occasion contributed the whole of his property and on another Hazrat ‘Uthman(ra) contributed almost the whole of his belongings, so that in accordance with this teaching the needs of the people were fulfilled according to the requirements of the age.

When during the time of the Khulafa’ the boundaries of the Islamic State became wider, the needs of the poor were fulfilled in a more organised manner. In the time of Hazrat ‘Umar(ra) regular records were maintained of the whole population and the necessities of life were provided for everybody according to fixed scales. In this way, everybody, rich or poor, was adequately provided for, and the means adopted were suited to the circumstances of those time. People are apt to imagine that the principle of providing the necessaries of life for every individual has been invented by the Bolsheviks. This is incorrect. This principle was laid down by Islam and was given effect to in an organised manner in the time of Hazrat ‘Umar(ra). Under the scheme originally introduced by Hazrat ‘Umar(ra), a breast-fed child did not qualify for any relief. The treasury became liable to provide relief for a child only after it had been weaned. In one case a mother weaned her child prematurely in order to be able to draw an allowance in respect of it from the treasury. Hazrat ‘Umar(ra) was going his rounds one evening when he heard a child crying in a hut. ‘Umar(ra) went in and inquired why the child was crying. Said the mother, ” ‘Umar(ra) has made a law that an allowance can be drawn for a child only when he has been weaned. I have stopped suckling the child to draw an allowance on his behalf; so, that is why he is crying.” Hazrat ‘Umar(ra) — and he himself related this incident — says that on hearing this, he blamed himself strongly lest by laying down this rule he may have interfered seriously with the physical growth of the next generation. He immediately issued a direction that an allowance should be payable in respect of every child as soon as born. This was the arrangement in ‘Umar’s(ra) time and again it was quite adequate having regard to the circumstances at that time. It is true that at that time the gulf between riches and poverty was not as wide as it is today. Zakat, voluntary contributions made to the State for the purpose, and private charity, these three afforded adequate and timely relief to the poor. There was no industrialization, and commercial competition was not as keen as it is in modern times. Powerful States did not exploit weaker States as they do today. The system that proved adequate in those times would prove inadequate and ineffective today. But this does not detract from the excellence of the Islamic teaching on the subject. At that time the object of this teaching could be fulfilled by means of Zakat and voluntary contributions, and it did not become necessary to have recourse to anything further. Today Zakat and voluntary contributions do not seem to suffice and some thing more is called for.

Today the world has become much more organised, and States are being daily driven to the adoption of policies which should give them greater and greater control over national wealth. If any of the movements to which I have drawn attention becomes supreme, the necessary result would be that individual wealth will be reduced and the greater part of the national wealth will come under the control of the State. The countries in which the successful movements originated and those allied with them may attain to greater happiness and peace, but other countries will be exploited and will be faced with greater misery and suffering.