Laws of Inheritance – Hoarding Banned – Prohibition of Interest – Zakat and Voluntary Charity – Personal Ownership – Superiority Over Bolshevik Principles – Capacity a Form of Capital – Social Inequality Under Bolshevism – Loss of Brains to the Nation – Danger of Rebellion

The principles I have just explained are designed to secure international peace. In the absence of international peace, it is not possible to secure conditions of national progress. But even after peace has been secured, it is necessary to carry out improvements in national conditions. I will, therefore, now turn to the means adopted by Islam for securing improvements.

With this object in view Islam has put forward four principles every one of which is designed to secure a more equitable distribution of wealth. One of the principal causes of social inequality is the accumulation of property and wealth in a few hands, so that the common people are deprived of all chances of acquiring property for themselves. To deal with this evil Islam compulsorily distributes property among a large number of heirs. On the death of a Muslim, his parents, widow, sons and daughters, all succeed to their shares in the property left by the deceased. Nobody is at liberty to modify in any manner the share to which each heir is entitled under this system. The Quran says that any attempt to interfere with this system is sinful. As compared with the Islamic system of inheritance, other systems suffer from various defects. Under some of them landed property is inherited by the eldest son alone, and under others females are excluded from inheritance by males. Manu, for instance, has laid down that daughters shall be excluded in the matter of inheritance by sons. Under all these systems property is confined in the hands of a comparatively small section of the community and the poor sections are deprived of all chances of improvement in their economic condition. As against this, Islam teaches that unless property and wealth are widely distributed, the community as a whole will not be able to progress. Under the Islamic system if a man has succeeded in accumulating property worth a lakh of rupees, it will be divided on his death among all his children, his parents (if still alive) and his widow if she survives him. In the course of a couple of generations, the original patrimony will have been so divided and subdivided that everyone of the numerous heirs of the original propositus will be compelled to exert himself to earn a respectable living instead of wasting his talents and living comfortably with the help only of inherited wealth.

Secondly, Islam forbids the hoarding of money, that is to say, it directs that money should be constantly in circulation. It must either be spent or invested so that it constantly fulfils its primary object as a means of exchange, and should promote commercial and industrial activity. A contravention of this direction is regarded by Islam as entailing grave divine displeasure resulting in dire penalties. There is a verse in the Quran which says that those who accumulate gold and silver in this life will be punished by means of the same in the life to come. The significance of this is obvious. If people were at liberty to accumulate money and precious metals which are the equivalent of currency, so much wealth would be withdrawn from circulation and, as a result, the community at large would be so much the poorer. If money is put constantly back into circulation, it helps to promote beneficent activities of all kinds, and thus serves to relieve poverty and distress by providing employment and stimulating effort. Take a simple illustration. If a person having a certain amount of money decides to build a residence for himself, or so construct a building for a public purpose, then, apart from the achievement of his object, he will by this means have provided employment for a number of brick-layers, masons, carpenters, iron-smiths, and so on. This would not have been the case had he merely kept the money locked up in his house or in a bank. Even in the case of Muslim women, although Islam permits them to wear ornaments, it discourages the expenditure of large amounts of money for this purpose.

Thirdly, Islam forbids the lending of money on interest. The institution of interest also results in accumulating wealth in comparatively fewer hands. It enables people with established custom and connections to go on multiplying their wealth practically without limit to the detriment of the rest of the community. Those of you, who are engaged in agriculture, can realise full well how a portion of the earnings of a peasant finds its way into the coffers of the money-lender. Under an economic system which could have made provision for agricultural credit on some basis other than that of interest, the peasantry in this country would have been very much more prosperous than it is today. Under the system now prevalent once a peasant is compelled to borrow, all his savings are absorbed by interest on the loan, and even after he has repaid the amount of the loan, many times over in the shape of interest, the original loan still remains due from him. Interest is, therefore, a curse which like a leech goes on sucking the blood of the poor. If the world desires economic peace, interest must be abolished, so that wealth is not permitted by this means to be monopolized by a small section of the community.

It may be urged that the three principles to which I have so far made reference no doubt secure that property and wealth should be continuously divided and sub-divided, and money should be put into circulation so as to prevent its accumulation in a few hands, but they make no provision for the direct relief of poverty and distress. The answer is that Islam supplements these with a fourth principle by providing for compulsory levies and encouraging voluntary contributions for the relief of poverty. Under the institution of Zakat, it is the duty of an Islamic State to levy a tax of 2.5% on average upon all wealth and capital which has been in the possession or under the direction of an assessee for one year. The proceeds of this tax must be devoted exclusively towards the relief of poverty and the raising of the standard of living of the poor. It must be noted that this tax is to be levied not merely upon the income or profits, but on capital and accumulations, so that sometimes this 2.5% may amount to as much as 50% of the income or profits, and in the case of accumulations has to be paid out of the accumulated money. This also has the effect of encouraging investment, for, if a person has a certain amount of money accumulated in his hands or lying to his credit, he will have to pay Zakat on it at the rate of 2.5% per annum, so that gradually the money will begin to disappear in payment of the tax. Every normal person, therefore, is compelled to invest his money and to put it into circulation so that he may be able to meet the assessment out of the profit earned. This results in a double benefit to the community as it secures the circulation of wealth and thus provides employment for all sections and in addition secures 2.5% of the capital and the profits made for the benefit of the poor. Under the stress of war conditions many people in this country are beginning foolishly to hoard gold and silver with the result that the prices of these metals have risen very high. The poorer sections are being forced to part with what little of these precious metals they may have accumulated in order to provide for their daily needs, and sometimes merely because they are tempted by the high prices which at present rule the market. On the other hand, these metals are being hoarded by bankers, money-lenders and others who fear that in the case of a Japanese invasion of the country, currency notes would become valueless. They do not realise that in the event of a successful Japanese invasion they will be deprived of all their accumulated gold and silver. Whatever the reason, the price of gold and silver is being forced up and poorer sections of the people have had to part with even the small quantities of these metals which they had accumulated in the past. The Islamic economic system, however, recommends that money and wealth should be constantly in circulation and employed in the service of the community, and that all accumulations, capital and profits, should be made to contribute towards the relief of poverty and the raising of the standard of living. If the injunctions, laid down by Islam in this respect, are obeyed and carried into effect, the most miserly person would be compelled to invest his savings and thus make a contribution towards general prosperity, and in addition pay 2.5% on them towards the relief of poverty.

It must, however, be remembered that in spite of all these provisions, Islam recognises the right of private property and individual ownership. But it ensures that the individual owner should treat his property as a sort of trust and subjects the institution of private property to limitations and correctives which tend to reduce the power and influence of the wealthier sections of the community.

It may be asked, why should not the Bolshevik system be preferred to the Islamic system? The answer is that the object of an ideal economic and social system should be to bring about conditions of peace and justice and to promote the spirit of progress. The Bolshevik system brings about an upheaval by means of a sudden revolution which deprives at one stroke the propertied classes of all their wealth, and thus creates bitter resentment between different sections. To deprive a wealthy person of his house, property, money and other forms of wealth is bound to administer an unbearable shock to him and to plunge him into misery and resentment. The bitterest enemies of the Bolsheviks are the aristocratic Russians who have been deprived of all their property and privileges and have been driven out of the country in a penniless and destitute condition. I had occasion to see some of these Russians during my stay in Europe, and I found that they were bitter enemies of the Bolshevik State. The reason is that from luxury they were instantly driven into penury and privation. It is true that a large share of their wealth should have rightfully belonged to the poorer sections of the people of their country, but generation after generation these people had believed that they were entitled to the ownership of their estates and other property, and when they were forcibly ejected therefrom, their reaction was very bitter indeed. That is why the Holy Prophet(sa) of Islam has said that old established titles should not be upset; that is to say, people with such titles and properties should not be subjected to treatment which should make them feel that they were being cruelly treated.

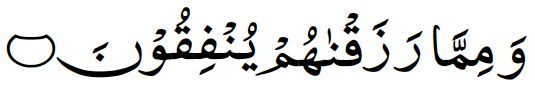

Secondly, Bolshevism ignores the fact that intellectual capacity is as much an asset as property and wealth. It exalts manual labour at the expense of intellectual effort, and it is a natural principle that whatever is not properly appreciated begins to decline. Those who do not value money soon run through it and those who lay no store by property are soon left without any. In the same way, people who do not appreciate intellectual effort begin to decline intellectually. The Bolshevik system is, therefore, subject to the serious drawback that by failing to recognise intellectual capacity as a valuable asset it discourages intellectual effort which is bound to lead to intellectual degeneration on a national scale. The reason why intellect is not regarded as a valuable asset by the Bolsheviks is that they are unable to subject it to compulsory equal distribution and to deal with it as tangible property. As against this, Islam brings about a gradual change and transformation and secures by gentle persuasion the application of all manner of talent and property in the service of mankind. By this means it succeeds in procuring a distribution not only of tangible property but also of intellectual capacities. In this respect even nature operates in opposition to the Bolshevik system. Nature endows different persons with different kinds and degrees of intellectual capacity, and the Bolsheviks have discovered no method of bringing about an equal distribution of this asset. Islam secures an equitable distribution in this respect also by directing that intellectual capacities also should be devoted to the service of humanity. The Holy Quran says:

“And spend out of what We have provided for them;” (2:4).

That is to say, those who believe sincerely and are anxious to attain nearness to God go on spending whatever We have given them (whether by way of intellectual and physical capacities or by way of wealth and property) in the service of mankind. (2:4). Thus Islam secures a distribution of all kinds of capacities and wealth not by force or violence but voluntarily through persuasion. This method secures all the benefits resulting from a general application of all talents and property to the service of mankind and being perfectly voluntary it leaves no sense of bitterness or resentment behind.

In spite of its high-sounding principles, Bolshevism has not succeeded in bringing about perfect equality in practice. In Russia even under the present system there are differences between the high and the low and between the rich and the poor. The most passionate advocate of Bolshevism will not claim that perfect equality has been achieved in Russia in all respects. Surely a peasant in the country districts does not eat the same food as those in authority in the bigger towns. On special occasions state banquets continue to be held and money is spent lavishly upon them. Only a short while ago when Mr. Wendell Wilkie went to Russia a banquet was given in his honour at which, according to press reports, sixty courses were served and Stalin and other Bolshevik officials who were present must have partaken of them. According to Bolshevik principles every citizen of the capital, as a matter of fact, every one of the 180 million people of Russia, is entitled to ask that these sixty courses should be provided for them also. It will be said that this would be impracticable and that exceptions must occasionally be made. But this would apply all over the field. If exceptions must occasionally be made and some distinctions must be tolerated, why upset the whole of society in a futile effort to abolish all distinctions? Why not try and bring about an equitable state of affairs in a manner which creates no bitterness?

Another consequence which is bound, in course of time, to come upon Bolshevism is that the country will begin to lose the benefit of the intellectual effort of its best brains. When Russian scientists and technicians find that they can derive no individual benefit from their intellectual activities, they will begin to find excuses for leaving the country and settling down in countries where the result of their researches may find better recompense and appreciation and bring higher individual reward. This will mean that other countries will benefit from the activities of the keenest Russian intellect, but Russia herself will be deprived of them. This tendency may not be apparent at this stage but is bound to manifest itself later on. Bolshevik principles sound very attractive just now, as the country had emancipated itself only very recently from Czarist tyranny, but as time passes their practical deficiencies will begin to press themselves upon the attention of the people. Bolshevik principles are very much like the teaching of the Bible, that if a person is smitten on the right cheek he should present the left one to the one who smites. This sounds very attractive so long as it is not put into practice. But if an attempt is made to act upon it, it is soon discovered to be entirely impracticable. It is related, that a Christian missionary used to preach in the streets of Cairo how full of love and tolerance the teachings of Jesus were. He would cite the injunction to turn the left cheek when the right one is smitten as an example, and make unfavourable comparisons with the teachings of other faiths. His discourses were couched in a very fine language and his audience used to be greatly affected. A Muslim, who had heard the missionary preach in this fashion on several occasions, became much upset. He wondered why no Muslim divine cared to tackle the missionary on the comparative merits of Islamic and Christian teachings. One day while the missionary was in the middle of his discourse this man approached him and expressed a desire to speak to him. The missionary inclined his head towards him to be able to listen to what he had to say. But the man instead of saying anything gave the missionary a violent slap on the face. The missionary was taken aback for a moment, but then fearing lest the man should proceed to further violence, raised his own hand in order to strike his assailant. The man remonstrated with the missionary and pointed out that he was expecting that in accordance with the Christian teaching, the missionary, instead of preparing to strike him in return, would turn his other cheek towards him. The missionary said, “I have decided today to act upon the teaching of the Quran, not the Bible.”

Some doctrines may seem or sound very attractive but prove entirely impracticable when tried out in practice. The same is the case with Bolshevism. There is great enthusiasm in support of it at the moment on account of its contrast with the tyranny of the Czars from which the country has only recently been rescued. Once that is forgotten, the natural desire to reap the benefits of one’s labour and effort will reassert itself and the newer generations will begin to rebel against the system of dead uniformity which Bolshevism seeks to impose, and all sorts of evils will begin to manifest themselves. As against this, the Islamic system, being perfectly voluntary and natural, never leads to rebellion though people may often fall short of its teachings in practice.